Collective Bargaining

Whether because of financial winds or political agendas, rarely has progress followed a clear path for the MTS. It’s dealings with the provincial government of the day to local school boards ran front a spirit of cooperation, negotiation and compromise to fierce defiance and resolution.

In 1919 the “militancy” associated with unions and demonstrations was new for teachers in Manitoba, but it was catching on elsewhere. The Winnipeg General Strike took place only 23 days after the founding meeting of the Manitoba Teachers’ Federation but there was no mention of it in any issue of The Bulletin.

In contrast, much of the initial progress of the MTF was due to the firm but even tone that characterized its leadership and earned the organization respect and credibility among trustees, politicians and policy makers. Within their first year, the Federation was affecting change.

The salary schedule just issued by the Winnipeg School Board forms the culmination of the work of the Salaries Committee of the Winnipeg Branch of the Teachers’ Federation… More than forty meetings of the committee were held. Their first task outside the committee room was to obtain an agreement that salaries should be the subject of conference between a committee of the School Board and a committee of the Federation. – The Bulletin, Oct 1920

Also in 1920, a Board of Reference was formed where the federation was represented equally along with trustees and the Department of Education. Bolstered by real progress, the MTF Legislative Committee also began work on a model contract with issues such as tenure and dismissals receiving considerable attention.

These were significant gains in a short time but solidarity was about to be tested. In 1922 the Brandon school board imposed a blanket 25 per cent wage reduction and a “take it or leave it” ultimatum. Some say all 80 teachers, including the Principal of Brandon Collegiate and even the Superintendent of elementary schools, resigned en masse, while others use the term fired. But, for the record, there was no strike. In a show of support, teachers from across the province and beyond sent in money to help tide over those affected until they could find other positions. Just as importantly, no members of the Society filled any of the vacancies.

The Brandon situation was high profile, but they weren’t the only one to test the will of the newly organized teachers.

The Board of Reference filled a real need, but for only three years. When two school boards refused to bide by its decisions, lawyers found that the decisions did not have the force of law, and the Board’s usefulness ended. (Not permanently; in 1934 its decisions were made legally binding.) – Chalk, Sweat and Cheers.

In another case of two steps forward, one step back, the Federation and Winnipeg teachers’ local found itself embroiled in a bitter dispute with the 1927 school board over the meaning of the word “conference” as it pertained to discussions about salary quoted above. On the upside, the first teacher pension plan was negotiated in 1929 and the Department of Education began providing school boards with the general contract that had been in development for nearly a decade.

Negotiating power was reduced to so much dust during the depression, so the MTF concentrated on building trust and goodwill among members, providing assistance, advice and even emergency funds while fees were reduced to a trickle and many members couldn’t pay at all.

When the worst was over, teachers remembered and returned in great enough numbers for the Manitoba Teachers’ Society Act to pass in 1942. With the act came automatic, though not compulsory, membership but there was no real advantage gained as far as bargaining power.

Two years later, the Privy Council Order-in-Council 1003 passed giving legal recognition of the rights of workers to organize, bargain collectively, and to strike. Legislation guaranteeing those rights in Manitoba (the Labour Relations Act) wasn’t adopted until 1948. In the meantime, there was even a vote in December 1945 at the annual Fall conventions over whether the MTS would become affiliated with a labour union. Only a slim majority voted against it.

From the time of the formation of the Manitoba Teachers’ Federation to 1948 there was no legislation that governed teacher collective bargaining. During this time, negotiations evolved through customary practice in some areas of the province, but collective bargaining was not common. Salaries and working conditions were determined by individual bargaining or by unilateral decision by school boards. Teachers might request a review of their salaries but this and other pertinent matters were unilaterally dictated by trustees. – Teacher Welfare -A brief History and Lessons Learned

When compulsory collective bargaining came into effect, some trustees began a campaign to have teachers excluded from the LRA, arguing that they belonged under the Public Schools Act. This splinter group did not represent all trustees however, and most teachers were not as concerned over what legislation they came under so long as their right to collective bargaining was guaranteed.

MTS and Manitoba Association of School Trustees presented a joint brief to provincial cabinet on June 6, 1955. The following year The Public Schools Act was amended to provide for collective bargaining rights for teachers, security of tenure, and the deduction of fees at source. Giving up the right to strike was a contentious point and a source of considerable division within the society with lines drawn between rural and metro associations. Teachers had never exercised the right since 1948. In the end, a unified society accepted binding arbitration as a fair alternative.

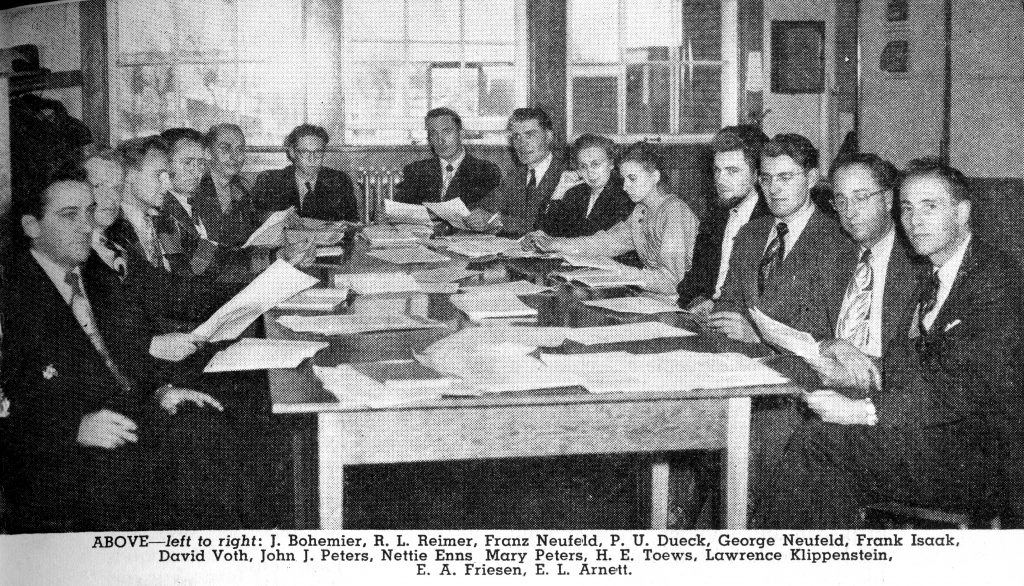

With MTS being the sole union, it was able to organize the bargaining units but by law the actual negotiations were between school boards and individual teacher associations. Teacher Welfare organized bargaining seminars twice a year which focused on salaries and economics as part of an overall regional plan to assist the many units (in the hundreds) that bargained.

The 1960s marked a period of real salary growth and bargaining gains, but the 1970s were far more challenging. Layoffs, an increase in part-time work, increases in multi-grade classes, larger class sizes and overall higher workloads became the new norm. In 1975, to deal with escalating inflation, the federal government passed the Anti-Inflation Act introducing wage and price controls which affected collective bargaining across Canada. The Manitoba Conservative government was keen to apply those measures to teachers’ salaries and the Society fought back with vigour not to be seen for another 20 years.

True to the pattern of ups and downs,, the 1980s brought about positive arbitration awards; duty free noon hour, hours of work (student contact time), and limitations of extra-curricular activity. In 1989 after more than 12 years of unsuccessful negotiations, one other article was imposed by arbitration – paid maternity leave.

If ever there was a moment that encapsulates the 1990s, it had to be the introduction of Bill 72 which intended to severely limit the rights of teachers in bargaining.

MTS held meetings across the province and in many cases got over 70 per cent of teachers in association to attend these meetings.

At the dawn of a new century, labour relations calmed under a new government. Teacher bargaining returned to the LRA for the first time since 1956.

The one significant change was the progressive growth of having MTS bargaining staff at local associations’ negotiations’ tables, especially in rural Manitoba.