Technology in the Classroom –

WITH EACH GENERATION, A REVOLUTION

If ever there was a common thread in education these last hundred years or so, it is technology in the classroom.

Each incarnation of the newest trend in teaching tech – from radio, to teaching machines to iPads — has been met with a mix of enthusiasm and condemnation by educators as well as the general public.

Along the way the Society has been a voice of moderation, speaking on behalf of the interests of both students and the profession.

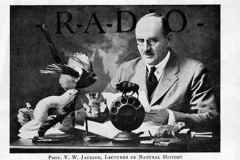

Within a half dozen years after the union was established in 1919, the first of many revolutions came over the air waves. It was, literally, a voice in the wilderness for hundreds of teachers around the province and they had Miss Lila Staples to thank for it.

The long-time history teacher at Kelvin School spearheaded the weekly programs aired through CKY starting in the spring of 1925. As head of the committee, she was instrumental in recruiting urban teachers to prepare high-school level programs on topics ranging from literature and music to science and history.

Schools, or listening groups if the radio lesson was outside the classroom, were urged to have a recording secretary report on the number of listeners each week. Teachers as well as the general public submitted letters of praise and thanks from across the province, although there were naysayers too in the debate over the place of such daring innovation. Peering far into the future of 1950, some predicted the teacher would be replaced with no more than a speaker at the front of the room. Later, the Department of Education would take over the work of arranging broadcasts for another 30 years or so.

By the time television was common in living rooms around Manitoba, radio programs were still around but mostly used in rural, elementary school settings. Having seen the benefits of broadcasts in schools, television should have been an easier “sell” but if the number of articles the Manitoba Teacher ran on the topic is any indication, there was plenty of discussion. To be fair, it wasn’t so much a question of whether or not television should be used in the classroom, but how and to what extent.

“When first considering TV, some questions seem almost automatically to come to mind. Can TV really teach? Is it just automation in education? Does it destroy the teacher/ pupil relationship? Is it a threat to teacher security? Is it expensive?”

“In the matter of teacher/pupil relationships what, indeed, do most of us dealing with 35 and more children per class in our urban secondary schools have to lose? Even here, however, a “closed – circuit” system can permit the specialist teacher to maintain his pupil contacts and relationships.” Manitoba Teacher- 1958

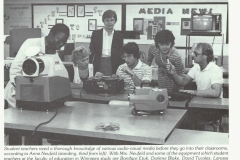

The MTS created an Ad-hoc educational television advisory committee in the early 1960s which included union activist and educator Sybil Shack. As principal of Isaac Brock School, she was actively involved in school broadcasting for many years and, if not the very first school in Winnipeg to have teachers prepare and broadcast TV lessons, Isaac Brock was a pioneer. Others like Tec Voc followed, but overall, in-school studios were uncommon given the cumbersome equipment of the day and complexities of editing and airing the programs.

If anyone was concerned – and again there were a few – that teachers would be replaced by a cold, talking box, they were soon relieved. While educational television in Manitoba began with great promise in the mid-1950s it never reached the kind of diverse programming and ease of access hoped for. There were numerous problems; a maze of bureaucracy within government, broadcasters and producers, constantly changing hardware requirements, and value for tax dollars. In other words, many of the same concerns teachers and administration have encountered time and again, right into the modern times.

Still, the use of video technology became embedded in schools. The influence of TV news in particular gained a foothold, but the source of programming evolved beyond the scope of that provided by the department of education.

At the dawn of a new century, corporations were eager to get their commercials in front of the young captive audiences in Manitoba schools. They offered free equipment to schools if they would show their Youth News Network to students. The Manitoba Teachers’ Society was a big part of the successful fight to keep YNN and its corporate-branded messages out of schools.

Then came the Internet.

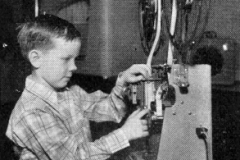

Even though computer applications in schools began in the 1970s for administration and specialized computer courses, classroom integration didn’t begin until the early 1980s. Once the microchip revolutionized processing, the age of personal computers was upon us.

Recognizing the revolutionary impact of computers on education and society generally, the Society’s Provincial Executive on June 12, 1981, established a task force on the implications and use of computers in education. The task force has been assigned to:

• compile information on current technological advances;

• examine applications of electronic technology, such as Telidon and Videotex;

• study the implications of the use of electronic technology for Manitoba teachers;

• and make recommendations for Society policy and activities toward the use of computer education.

The work of the task force should alleviate fears that “the chips are down,” as some teachers have suggested. The notion that teachers will be replaced by computers and their training has become outmoded does not have to come true. Instead, through the work of the network, Manitoba teachers will have the opportunity to develop a balanced perspective on the role of computers in society, establish policy on the appropriate use of computers in the classroom, and view the revolution in computers as a chance to be in the chips.“ – The Manitoba Teacher -December, 1981.

Aside from the usual problems of hardware and infrastructure, the use of computers led to new questions of access and equality, especially from the standpoint of regions within the province and even among divisions. Much like the first days of radio, virtual classrooms and distance education have been a boon to students and teachers alike, but modern questions of copyright over lesson plans and the value of work done under contract became a concern to the Society. Likewise, the recurring warning that teachers could be replaced altogether by a talking screen has died down but the very real consequences of technology, positive and negative, have been the topic of countless PD sessions, and addressed in collective agreement seminars.

Today’s environment harkens back to the television era where the question is not whether the current technology belongs in the classroom but how and to what extent and how it impacts a teacher’s relationship with students and even parents. In this capacity the society’s role is, as always, to keep the dialogue open and moving forward with the best interest of students and teachers top of mind.