Where it all Began

It was April, 1919.

The Great War had ended just five months previously. The Manitoba Liberal minority government of Tobias Norris was hanging on with support of the progressive United Farmers of Manitoba . In two months, the first transatlantic flight would leave Newfoundland. In a month a general strike would paralyze Winnipeg.

Amid the unfolding of history, a group of teachers were working to bring a long-held vision to reality. They envisioned an organization of teachers that would protect its members and bring order to what they saw as the “chaotic state” of education.

At the time teachers were hired and taught and were fired at the whim of school division officials spread out in the more than 2,000 districts across the province. If a single female teacher got married, they were fired. Many had to live where they were told. Some taught with the most threadbare qualifications. Barbers earned more than teachers.

Almost a year earlier, on a hot June day in 1918, W.E. Marsh, a Belmont teacher, gathered 17 of his colleagues together in the basement gymnasium of the old Normal School on Winnipeg’s William Avenue to discuss forming a teachers’ organization.

Marsh and his fellow teachers met over lunch hour to pool their resources and lay the foundation for what was to become the Manitoba Teachers’ Federation (MTF).

They recognized that teachers’ wages, along with those of other workers, were paltry. They also knew they were sowing the seeds for something bigger than themselves.

The following year, on April 22, 1919—at 7:30 p.m. to be precise—hundreds of Manitoba’s teachers poured into the concert hall of the Industrial Bureau at Main and Water Streets to organize themselves at their first general meeting.

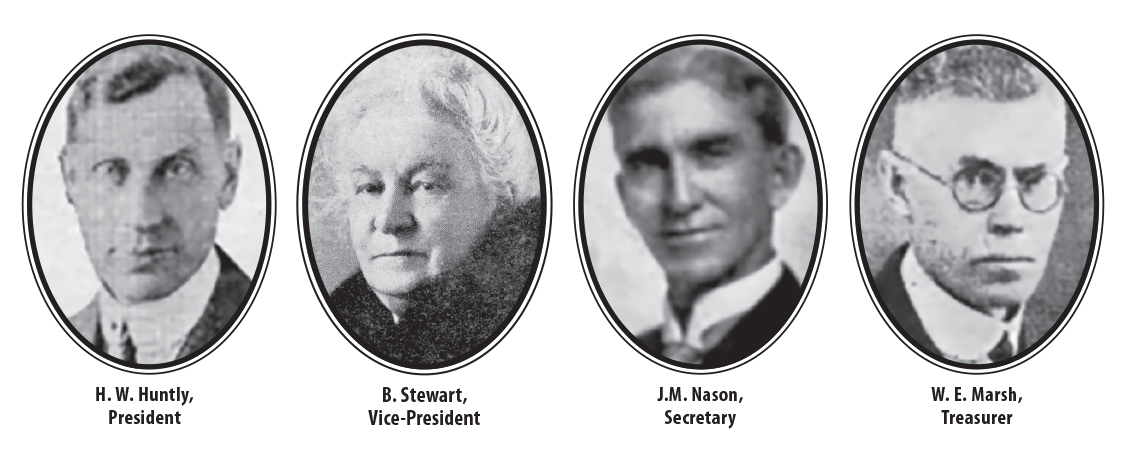

The first officers of the organization included men and women from across the province, from Winnipeg to Teulon to Brandon and Souris.

The Bulletin, the forerunner to The Manitoba Teacher, reported that a constitution had been drafted and accepted at the meeting.

“Before the meeting on April 22, there were about 200 members. At the close of the convention on April 24, there were 600. There are now over 700 members, 10 local associations already formed and affiliated and many in the process of formation.”

One of the first efforts was to encourage teachers to form local associations. A one-time registration fee of $1 was set along with a yearly fee of $2 for members. Locals were allowed to add “a small fee for its own expenses, such as postage, stationary, etc.”

“We have our Federation, but all have not yet joined up … and as our success depends largely on our numbers, we appeal to you to ‘sign up’. In this spirit of mutual trust, fired with the idea of exercising the most potent influence for good in the community, let us accept the challenge.”

The following issue of the Bulletin in September emphasized the need for teachers to organize locals, setting out a goal of having the complete province organized in that school year.

“We are confident that the claims and objects of the Federation have only to be placed before the teachers in order to enlist their hearty co-operation and support,” the MTF executive wrote.

“The most desirable size for the local is still a matter of debate. Probably only experience will show whether a local of seven, 70 or 700 teachers is most desirable. The present constitution calls for at least 10.”

The formation of what would become The Manitoba Teachers’ Society, while attracting widespread praise, also had its critics.

Federation secretary, J. M. Nason, acknowledged criticism in a Bulletin article.

“To the charge that we are Bolsheviki we wish to be perfectly understood that members of the executive are deeply in earnest and in the profession for its own sake,” he wrote. “If they can prepare the boys and girls of the present generation to go out into the world and fill their places as good citizens in the truest sense of the word they ask no higher reward, if only they can be assured of a proper living wage and working conditions which will not leave them physical wrecks after a few years of service.”

It wouldn’t be long before the Federation came face-to-face with its harshest critics. In 1922 nearly 80 of Brandon’s public school teachers were fired for rejecting a 25 per cent salary cut.

As J. C. Wherrett, one of those teachers, noted: “We felt that by taking a stand we had perhaps saved others from such an ordeal.” The Federation’s lobbying didn’t recover the jobs, but the MTF did come to the members’ financial aid.

Slashed teachers’ salaries and indiscriminate firings followed during the Depression. Membership in the MTF fell dramatically during this period as teachers left the profession. However, in 1934, the MTF secured a new teachers’ contract which better protected members.

Up to and during World War II, the MTF lobbied for larger school divisions to improve efficiency. In 1942, the MTF became The Manitoba Teachers’ Society (MTS) in recognition of its responsibility for teachers’ professionalism and ethical conduct.

The struggles, big and small, continued through the decades with gains from a set school day to parental leave and equal pay for men and women.

As the Society turned 100, other issues had supplanted those of history. But the work and the vision continues.

As was written when the organization was first formed:

“For let it be remembered that what this Federation is trying to do, is to build out of the conditions of things as they are what they should be.”