Teacher Certification

The term Normal School routinely elicits a perplexed chuckle these days, but for generations of teachers, graduation from one of the province’s training centres was the official start of their careers.

So named because of the emphasis on established “norms” of social and moral behavior for students and teachers as well as basic curriculum, the first teacher education institutions of Europe were established in the 17th century. At home, the Manitoba Teachers’ Federation was a driving force in bringing them into the 20th century.

When the MTF formed in 1919, there were four English Normal Schools in Winnipeg, Brandon, Manitou and Dauphin. Other such schools in Mennonite communities as well as the French, St. Boniface Ecole Normale were shut down in 1916 as the government of the day amended the Public Schools Act to a secular, monolingual system.

The entrance requirement was, ideally, Grade XII or Grade XI for particularly well-suited candidates, but students with no more than a Grade 9 were all too common. The Winnipeg and Brandon Normal Schools provided the one-year teachers’ course required for Second and First Class Certificates, while Manitou and Dauphin also offered a 12-week course and conferred to graduates a Third Class Certificate.

The Federation had numerous issues to contend with in its first few years but lost no time in seeking allies within the normal schools and the provincial Department of Education when it came to teacher training.

In what would be the first of many such presentations of its kind over the years, the MTF made its position clear to the 1924 Educational Commission. The September 1925 issue of the Manitoba Teacher reported, “The short-term Normal has at last disappeared from Manitoba. This change in teacher-training is likely to be very far-reaching not only in regard to the profession itself but in the broader matters of citizenship. At a meeting of the Advisory Board this spring the decision was finally made that the minimum training shall be a year’s course at a Normal School. … Whilst the change grew directly out of the recommendations in the report of the Murray Commission, it originated in representations made to the Commission by the Federation. We believe this to be an important advance in our educational system, probably the most important of the year.”

In 1929, the MTF announced with great satisfaction that permits and Third Class certificates were practically non-existent, while Second and first Class certificates were at an all-time high.

“Conditions in many parts of the province are such that it is impossible for some school districts to persuade a properly qualified teacher to take charge of their schools. The day will come when every child will receive equal educational opportunities, but until that day dawns, we must be content to allow an unqualified teacher to do the best he can.”

Of course, we know hard times were just around the corner. Entrance to Normal School was relatively cheap and anyone who left teaching for greener pastures in the past dusted off their certificate now. The abundance of teachers kept salaries lower than ever, but since there were not enough jobs, those who could afford to do so continued their education for a second year and added university courses, earning a First Class, Collegiate or even a Principals’ Certificate. Due to increased demand, and support not only from the MTF but within the Department of Education, the University of Manitoba established the Faculty of Education in September, 1935. For all the emphasis on higher education, the salaries of teachers didn’t reflect their improved qualifications and when the economy improved, many left the profession again. The result was a swift about-face in teacher supply that left the province scrambling to fill positions, especially in rural schools.

For the most part, the MTF had no issues with the Normal Schools themselves, save for insisting on higher entrance standards, but permits granted by the Provincial Department of Education was another matter. Allowing the unqualified to teach undermined everything the Federation was fighting for. The MTF supported the permittees; welcoming them into the fold, encouraging further study and giving credit where it was due since many taught in the most wretched conditions. Rather than ever admit the connection between professional status, training and salaries, the government of the day continued to issue hundreds of temporary permits, erasing the last 10 years’ progress by 1939.

In 1942, the organization, now called The Manitoba Teachers’ Society, celebrated the victory of having the Society recognized as the official voice of teachers.

Unfortunately, the government still wasn’t listening as reported in the Winnipeg Tribune of July 1944: “About 300 high school students, who recently graduated from Grades 11 and 12, are attending a special short course for teachers, which commenced in the University of Manitoba (Broadway) buildings this morning. This course, sponsored by the provincial department of education, will last six weeks, and is designed to meet as far as possible the serious shortage of teachers in Manitoba, authorities stated.”

Six weeks. If the abolition of the 12-week course almost 20 years before was one step forward, this ‘temporary’ measure was two steps back. The MTS opposed it but couldn’t be seen to criticize what was essentially a ‘war measures’ solution to keeping schools open. And when the war ended? The course persisted for over 10 years. It was then replaced by another to offset the shortage of high school teachers.

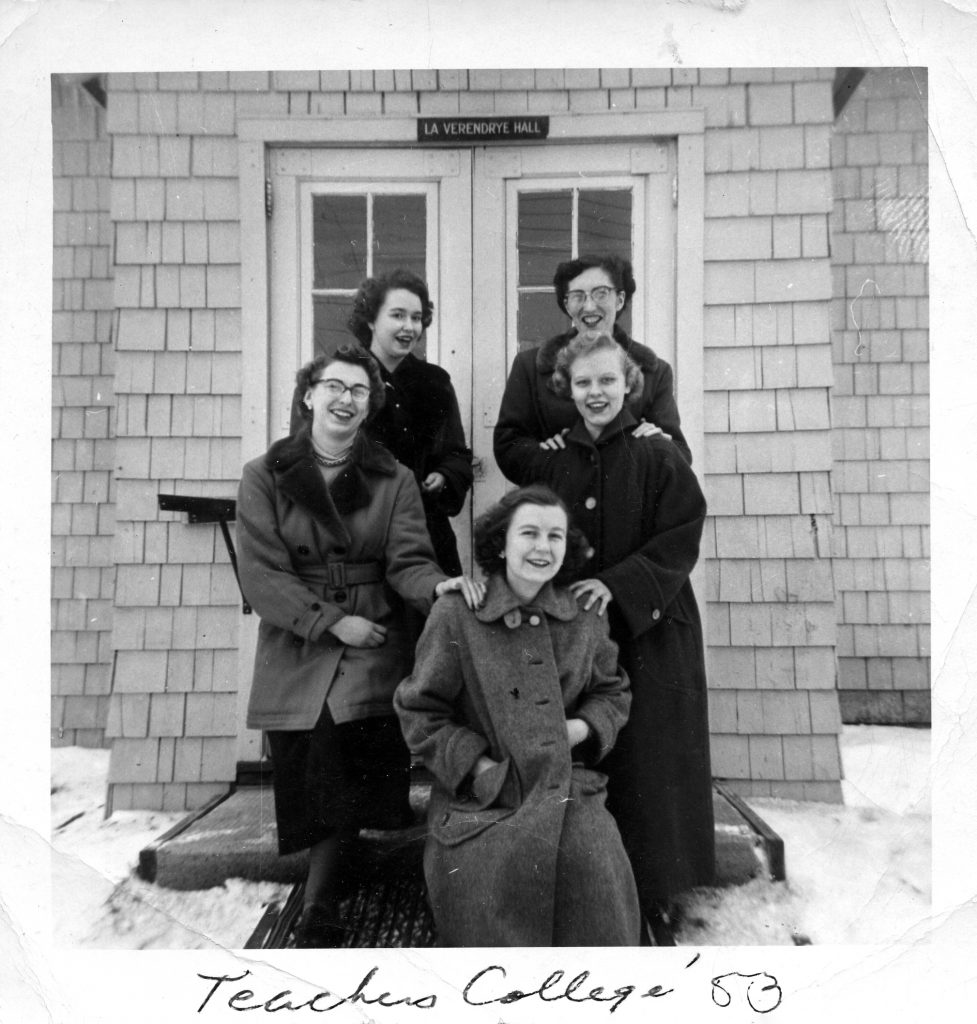

That ‘emergency’ 12-week course was offered from 1957 until 1971. The province attempted to re-brand the ongoing permit situation by calling them ‘student teachers’ just as it renamed the Provincial Normal School, the Manitoba Teachers’ College.

For many, their time in residence at the college brings back happy memories, but the two-tiered stream in teacher education kept Manitoba behind the times and undermined the value of a degree even when all teacher training came under the umbrella of the U of M’s Faculty of Education in 1965, The University of Winnipeg, 1968 and Brandon University, 1969.

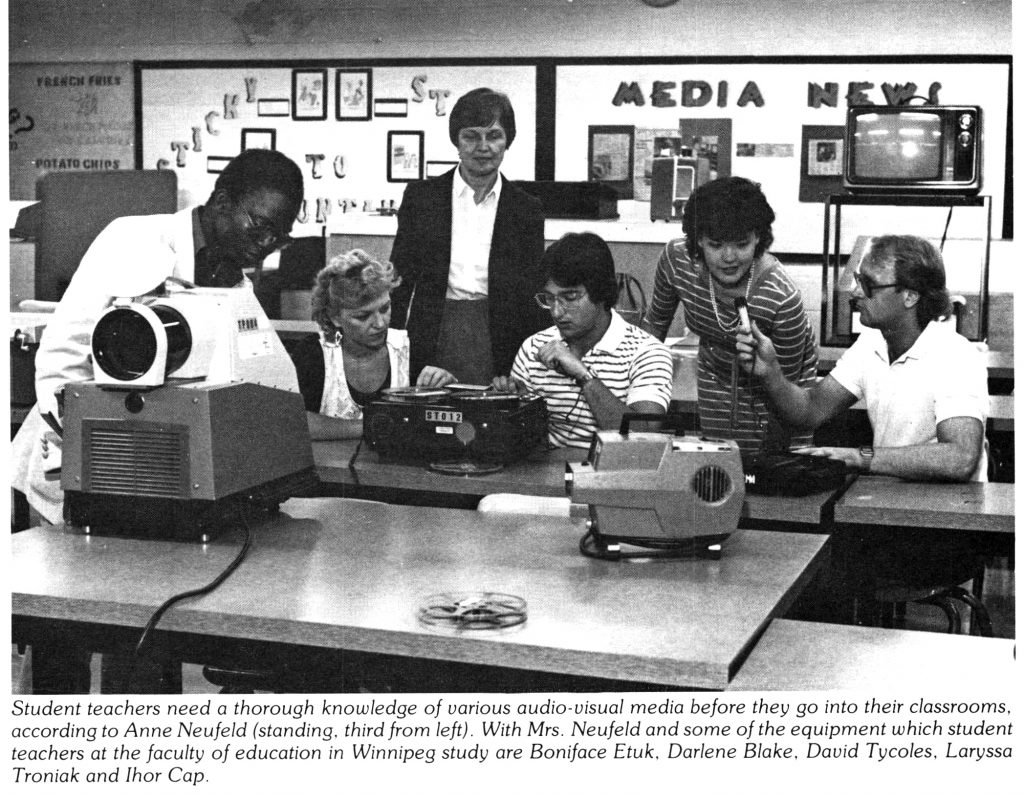

Throughout the 1970s, MTS pushed for more say in the content and structure of university courses and in the practicum of student teachers. Meanwhile, as issues such as differentiated staffing arose, Emerson Arnett outlined the MTS’ position circa 1973: “The Society, implicitly or explicitly, has established general policies on teacher certification.”

Those policies included that teachers’ certificates should be based on a four-year degree program, that teacher preparation is a life-long process and that preparation is a shared responsibility of MTS, the province and employer. MTS has been a player in teacher training and professional development since, ensuring MTS representation on a long list of boards, in organizations and on committees influencing everything from the selection of teacher candidates to disciplinary action affecting a members’ certification.